The New No-Man's-Land

On Ukraine's Eastern front Mykola lays clutching his stomach, where a Russian 7.62 bullet has bounced off his rifle and penetrated horizontally, mushroomed to the size of a jagged ping pong ball, severing his large intestine. He has been laying on Ukraine's Eastern front for 2 days as internal bleeding swells his stomach, hoping each night the correct conditions will manifest to extract him from the frontline, then transfer him to an ambulance, which can finally bring him to a field hospital.

Drones have changed the shape of war in Ukraine again. They are now the leading cause of death on the battlefield, and have made evacuating those that survive more dangerous than any war in modern history. The no-mans-land of WWI now lies not between Ukrainian and Russian lines, but behind them. Mykola’s trench is an island of 3 or 4 Ukrainians, their adjacent trenches, dozens or hundreds of meters apart are remote as distant planets. The 10-20 kilometers behind these trenches, called “The Grey Zone”, soldiers fear more than the frontline. It exists under a blanket of perpetual Russian surveillance, its atmosphere buzzes with the persistent presence of dozens of armed drones, while mortars, artillery, rockets, and aerial bombs can be unleashed in moments with deadly accuracy. The “Grey Zone” can only be escaped from, not survived in.

Traversing the “Gray Zone”, whether bringing new soldiers or supplies onto the front, or evacuating the Injured or dead, is considered the most dangerous part of this war by all those fighting it. Under ideal conditions, with a good vehicle, and only by night, the chance of any vehicle transiting this zone without being hit is 50%. To reduce the danger of transiting the “Grey Zone” Soldiers now frequently spend nearly a month on isolated frontline outposts without relief. Supplies are dropped from drones, and the dead hauled out by ground-drones. But the wounded who cannot limp off the front alone must still be evacuated, and at the risk of 2-3 more soldiers and their vehicle.

—REDACTED— Kilometers behind Mykola is a field hospital where Davinci Wolves combat medics, volunteers, surgeons and anesthesiologist wait for whatever casualties may limp, roll, or be carried into their surgery bays. They too are far from safety, Russians hit their previous position with 4 glide-bombs a month before, destroying it only days after they abandoned the position.

The Davinci medics at the Field Hospital spend their days sleeping and the narrow hours of summer darkness waiting, they hope, for nothing to arrive. They don't wait idle, and rarely in vain. While Davinicis' medical evacuations come with advanced warning, allowing the medics to pre-stage their bays for the specific injuries expected, often adjacent units send their injured here with no more warning than the sudden screech of car tires and a shout from the guards.

Having survived another night and day with his stomach loosely bandaged Mykola now faces the most dangerous period: leaving the front through the “Grey Zone”. If he can walk with internal bleeding, he will stumble alone from his frontline trench at night, potentially for many kilometers to meet a vehicle waiting at a safer distance. Russian drones will hunt him, and Ukranian surveillance drones will guide him from above.

If he cannot walk, he must hope a vehicle and its crew can be risked to extract him before he bleeds to death, or dies of infection, and then that he and the crew survive the drive.

Not far away the Davinci Medical Evacuation team waits on cots, armor by their side, swift Land Cruisers packed and ready outside waiting to transport casualties from the “Grey Zone” to the field hospital. They won’t depart until the last moment possible, when they can be sure the armored vehicle transporting Mykola has survived and their meeting point will only be exposed for the shortest amount of time.

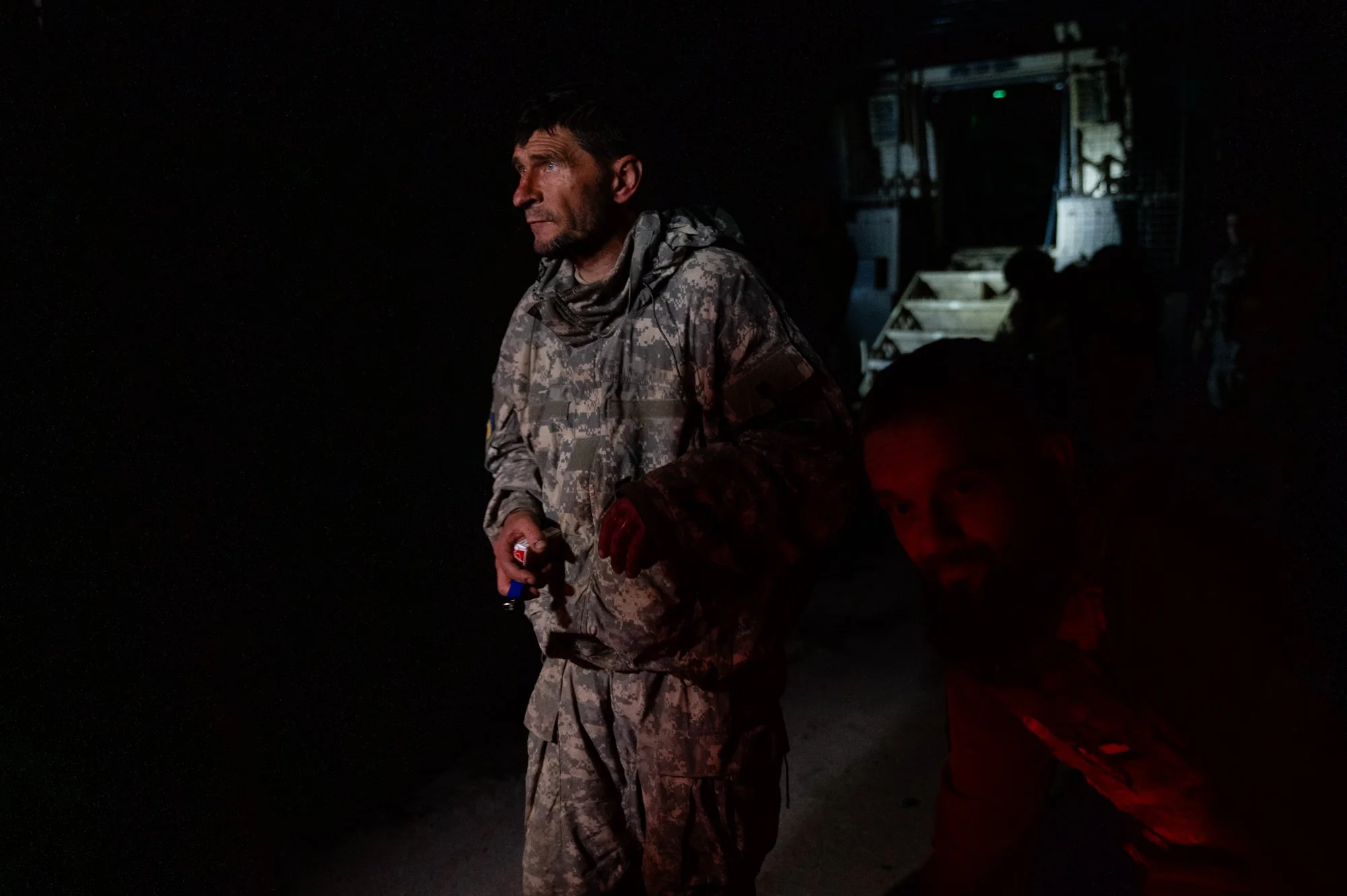

When the call comes the men have a speed polished by practice: Armor glides over the head, then closes to the front, boots are stepped into and cinched on, rifles on their chests. The meeting point has already been decided, along the way they race past their previous field hospital, smashed by bombs. A bit farther their old base: a civilian home, destroyed by drones.

The Davinci’s Medical Evacuation team has efficiency, training and equipment familiar to anyone who witnessed the “Golden Hour” evacuations of Iraq or Afghanistan, when most casualties where delivered to field hospitals by helicopter in an hour or less. This was considered a steady norm from the Vietnam wars 30 minuets, or 6 hours in the Korean War. Swift evacuation meant even horrific injuries had high survival rates, and concerns like hypothermia, infection, or tourniquet related injuries where relegated from the concerns of frontline soldiers. The mass use of cheap armed drones in Ukraine not only causes a majority of the casualties now, but has altered the battlefield dangers to the point that casualties must survive for days for a chance to be evacuated.

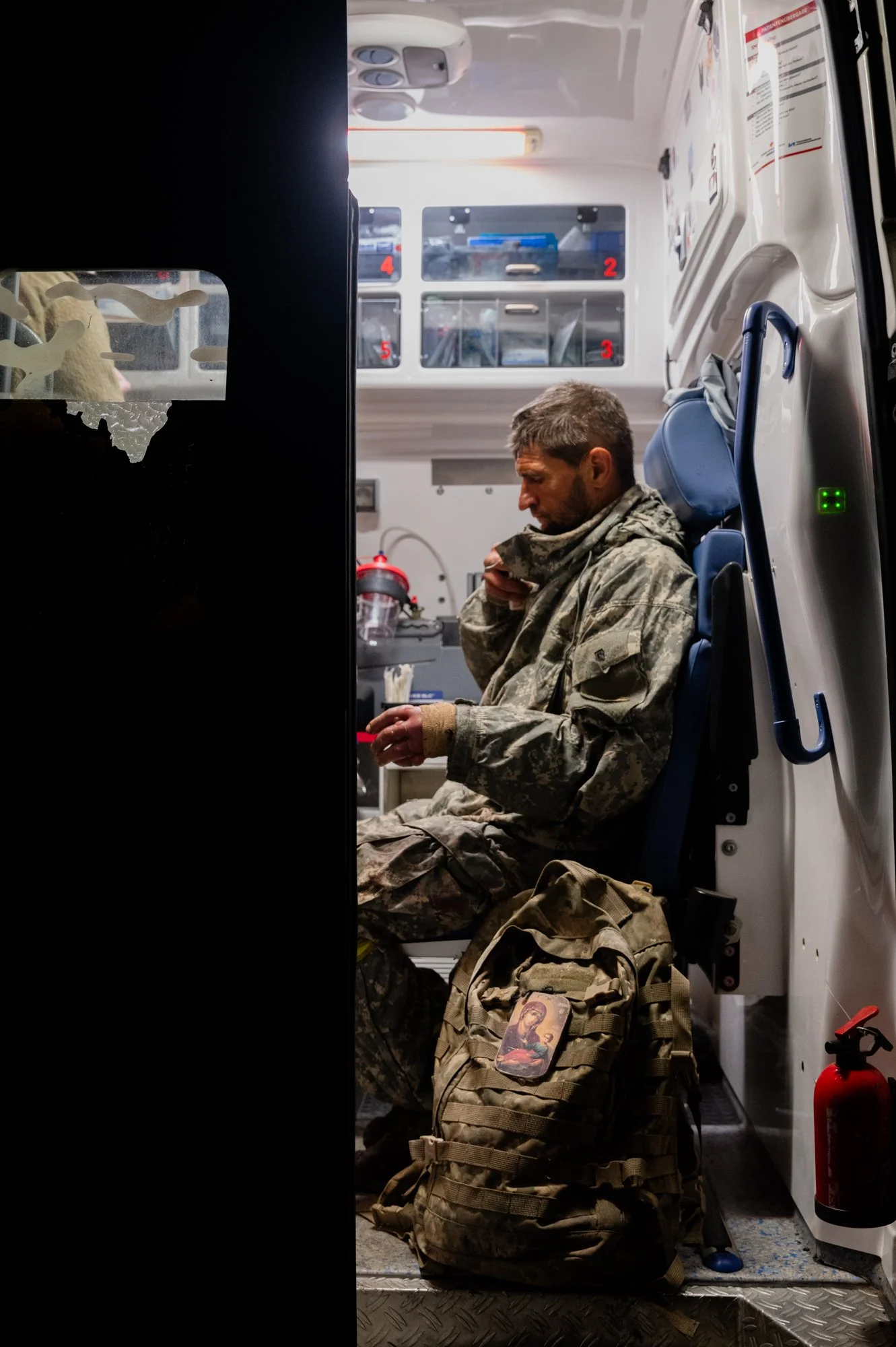

When Mykola finally arrives at the field hospital his injury is 3 days old. The ambulance door slides open to a wheelchair waiting for him. He hesitates, standing, yes, they insist. In the medical bay reserved for the more grievously injured Davinci medics wait, some manning computers and x-ray machine, two more to usher him onto a cot. A fatigued uniform is stripped off to reveal a bandage made of a reflective space blanket. Beneath a protrusion of intestine gleams out.

Mykola is standing again while the Davinci team x-rays him, the surgeon and Davinci medics review the results in real time. He is wheeled into a gleaming surgical suite where 9 doctors, surgeons, anesthesiologists and nurses are prepping. The anesthesiologist, a lone EarPod in administers a series of injections into the IV’s started by the Davinci medics. The lights in his eyes dim under the surgeon's LEDs, his brow unfurls and 5 of the medical staff lay him down, then begin prepping his body for the ordeal to follow, the white flesh of his stomach at first gleamed against the dirt and tan of his arms, now greased with orange brown antiseptic.

Mykola is now unconscious, swollen stomach gleaming. They open his stomach swiftly. There is the sharp smell of digestive acids, copper, almonds. Then burning hair: Cauterizing scissors are handed to the surgeon, smoke reefs form the wound. With his stomach now opened, his intestine is removed, then inspected inch by inch. A jagged starburst of a machine guns bullets is prized out, the nurse holds it to the light, goes to discard it along with the length of intestine, hesitates and places it next to the dirtied surgeons tools instead. Stomach examined, cleaned and sutured the doctors begin closing Mykola’s stomach.

Outside The sun is rising. There is talk of another Medivac for 3 soldiers from the 59th brigade's Squale Battallion. Assaulting a Russian position they took injuries and managed to limp to a Davinci position, with a prisoner in tow. Some of the medics wait, Some smoke, others hurry back to sleep, if there is a chance to evacuate them it won’t be until nightfall.

The following day Serhii Filimonov, The Davincis Wolves Brigade imposing commander, stands in the depths of a command bunker weighing the options, and the chances, of the injured Squale soldiers. There is silence for several seconds.

Filimonov knows the risk, and loss better than most: The unit's founder, namesake, and his closest childhood friend, Dmitro Kotsiubailo was killed during an evacuation attempt, an inescapable memory to thosewho knew him. His loss is both upheld as a demonstration of the loyalty the unit is famous for, and it’s cost.

“Probably they will die” Fillamonov says, his voice flat and unflinching.

He then says the latest attempted frontline extraction injured 3 Davinci soldiers and damaged an armored vehicle.

A successful evacuation requires the right conditions: a night with low Russian drone activity, reserve vehicles and men, the applied efforts of Davinci's Electronic Warfare Battalion shielding them from drones, a lull in the Russian assaults, and ideally, poor weather that limits drones range.

Davinci's Electronic Warfare Headquarters sits in a damp basement, “Commander” the appropriately nick-named second in command monitors a bank of screens displaying Russian drone feeds and dozens of jammed frequencies. What he can’t see is the wire guided fiber-optic drones Russia has adopted recently, a deadly unknown on the Eastern front. “Commander”describes their role “we are the defense of their attack. Our main mission is to defend the infantry in our zone, and to cover the evacuation vehicles”. Less drones, both surveillance and armed, work at night, combined with Electronic Warfare jamming efforts the Electronic Warfare team works to find, and create opportunities for evacuation.

The evacuation is planned for the evening. The Davinci medical team prepares two ambulances and a new rendezvous point. Idling onto an empty field the two ambulances wait for the distant rumbling of engines. In the rear compartments the medics review gear and pre-stage what tools they will likely need. The combined ambulance and armored vehicles make four attractive targets for Russian drones and bombs. A distant humm brings everyone to attention. Suddenly it stops, then radio traffic. THe Davinci crews take to their vehicles again lurching off. Just 300 meters farther they stop on the edge of a row of houses. A Hulking armored vehicle lurches onto the street and a crew member opens the rear hatch. Pale men in splattered uniforms gingerly descend its troop steps. There rifles and backpacks are gathered up and they are loaded into the waiting Land Cruisers. The only color to the men is the dirt and blood on there faces.

Arriving at the Field Hospital the Squale soldiers have been assessed during the drive. They are ushered one by one into the routine medical bay, there injuries are light. Lightest of all is perhaps the most worrying: successive explosions have left one soldier barely cognizant, unable to speak, and uncoordinated. The second soldiers’ hand lays in bloody bandages, the fingers emerging bubbling from intense burn blisters. The third refuses to sit, and when his trousers are removed a pool of blood drips from the crotch of his underwear. Painfully stripped away a neat entry wound reveals itself.

In a half hour the Davinci medics have them appraised and bandaged. Wearing ill fitting donated clothes the Squale soldiers huddle in a corner of the pale lit waiting room. Shaking out cigarettes they hesitate leaving the underground field hospital. The concussed soldier moves to the door, another pulls him back sharply, then holds him. Each lights up in turn taking several puffs before one cracks the door, and looks to the sky. They step outside into the last of the nights dark, inhale cigarettes and shuffle inside again.

Huddled again in the corner of a waiting room they discuss the Russian prisoner: they found him stuck in a steep, tank trap trench, trying to dig stairs out of its earthen wall to escape. He offered them no resistance so they pulled him out by his rifle.

Just before dawn a soldier from the 59th Brigade arrives in a silver hatchback. The hospital guard delivers to him the armor, weapons and packs of the injured soldiers, which he loads into the trunk alongside the hog-tied Shishlonov, 36 years old from Penza, Russia.

He joined the Russian 30th Motor Rifle Brigade 6 months ago, and has been in Ukraine for 3. He describes the rest of his platoon as “dead or injured”. When asked about his lack of Uniform he replies that he was never issued one. Shishlonov asks “what does Ukraine do with prisoners?”.

The 59th brigade soldier tells him he will receive 3 meals a day until he is sent home. Hat firmly taped over this face Shishlonov is unaware the dawn of the greatest day of his life is beginning to glow through the trees.

Reporting Dates: 5/18-5/24 2025